As a teenage cross-country runner, I believed that if I cut out dietary fat, I would reduce my body fat stores and therefore increase my speed. Besides, many other people around me were demonizing dietary fat, too. In those days, low-fat and no-fat were all the rage. The food industry was more than happy to capitalize on the fad, thus leading to grocery store shelves filled with fat-free products like SnackWell’s cookies, thereby perverting the notion that we were all on the right track to health while simultaneously enabling our disordered eating.

Unlike actual scientific evidence, popular-culture nutrition is fickle. The Atkins diet was hot while I was in nutrition school, but by the time I became a practicing dietitian, going gluten-free was the in thing to do. Hardly any of my patients back then actually knew what gluten was and where it was found, but they erroneously believed they had eliminated it from their diets and boy did they feel better.

Scarce are the people who fear dietary fat now, and these days fewer and fewer people seem wary of gluten, but now sugar is in pop culture’s crosshairs. This past weekend, Joanne played in a charity tennis tournament where she encountered a sponsor who was touting his sugar-free sports drink. “Sometimes people need sugar,” she reminded him, and also threw in that she is a registered dietitian. Offering a rebuttal that lands squarely at the intersection of pseudoscience and weight stigma, he offered, “Sugar makes you fat.”

Regarding the latter, I approached him by myself to see if he would make a similar comment to me, a male in a thinner body, but he did not seem interested in engaging me in conversation. “So, your product is essentially made to rival drinks like VitaminWater Zero?” I asked, but he just walked away. In fairness, he might not have heard me, as many players and staff around us were making quite a bit of noise.

With regards to the factual accuracy of his claim – or lack thereof – no, sugar does not make you fat; that is not how weight regulation works. Body weight is the result of many different factors, including, but not limited to: genetics, environment, medical conditions, and lived experience (for example, history of weight cycling). Eating and physical activity behaviors are of course part of the equation, too, but contrary to popular belief, our weight is largely out of our hands. In fact, a presenter at a conference I attended last year stated that weight is 90% as genetically determined as height.

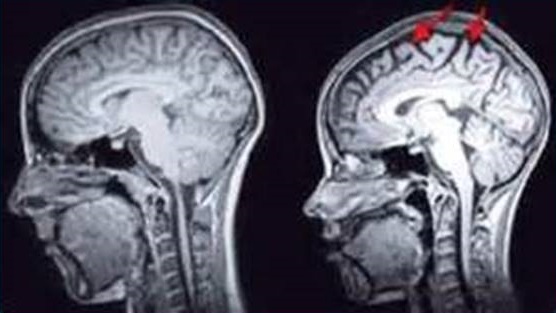

Besides, Joanne was correct; people do need sugar. Your doctor most likely measures your blood glucose, a kind of sugar, at your annual physicals. If that number reads zero, you are dead. Even if it merely slips below the normal range, you are probably lightheaded, lethargic, and having difficulty concentrating, all symptoms of not having enough circulating sugar to fuel your brain and other organs.

While the rate of the reaction depends on the food in question and one’s individual body chemistry, our systems eventually break all carbohydrates – from sprouted ancient grains to neon gummy bears – into simple sugars. You can get a sense of this by chewing a piece of bread or cracker longer than normal. The sweetness increases the longer you chew because the salivary amylase, an enzyme in your saliva, is already breaking down the long carbohydrate chains into sugar.

Besides, creating a sports drink without sugar is somewhat head scratching. On one hand, I guess it makes perfect sense, just as fat-free cookies back in the 1990s sounded like a great idea, too. Both are cases of smart food manufacturers taking advantage of nutrition fads to satisfy consumer demand and thereby earning themselves quite a profit. Always remember that a food company’s priority is their income, not our health; product prevalence is only a gauge of demand, not the state of nutrition science.

Sports nutrition, in particular, is an area where the fear of sugar is hurting athletes. Carbohydrates and fat are the main sources of fuel during athletics. Even the leanest marathon runner has enough fat stores to provide sufficient amounts during their event, but our carbohydrate stores are much more limited, as we only tuck away small quantities in our liver and muscles in the form of glycogen. If we do not replenish our carbohydrates during exercise, we pay the price, as I can attest from personal experience. As a long-distance cyclist, only twice in my life have I failed to complete rides that I set out to do. The first was when I fell off my bike in Montana and fractured my spine. The other was a few years later when I was temporarily experimenting with a low-carb diet and became so fatigued that I could not make it home.

Much more recently, I went for a 21.2-mile training run in preparation for next month’s Newport marathon and consumed nearly two liters of Gatorade out on the road. Thanks in part to the approximate 112 grams of sugar keeping my energy up, I had a great run and could easily have kept going for another five miles had it been race day.

Back when I was a fat-avoiding teenager, my mom saw the red flags of disordered eating and brought me to a dietitian who explained to me that, contrary to popular belief, dietary fat was fine to consume and that cutting it out would hinder, not improve, my running. Now that I am on the other side of the counseling table, hopefully I can give you similar reassurance about sugar.

You have seen memes and headlines suggesting that sugar is toxic and maybe you have questioned if you have a sugar addiction. Perhaps sugar-free products sound like the path to salvation and virtue. Attempting to cut out sugar might feel like the right next step, especially when so many people around you are going down that road, but I caution you against such pursuits. Remember, soon enough our culture will be demonizing another nutrient, ingredient, or food group. Better to establish and retain a healthy relationship with food and let the fads fall by the wayside.