“Anything is possibleeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee!” Kevin Garnett was already one of my favorite basketball players long before he came to Boston and helped the Celtics to win the 2008 championship, but his famous post-victory line made me cringe. No, Kevin, while I understand you were excited and trying to inspire, empower, and motivate, let’s be real: Anything is not possible.

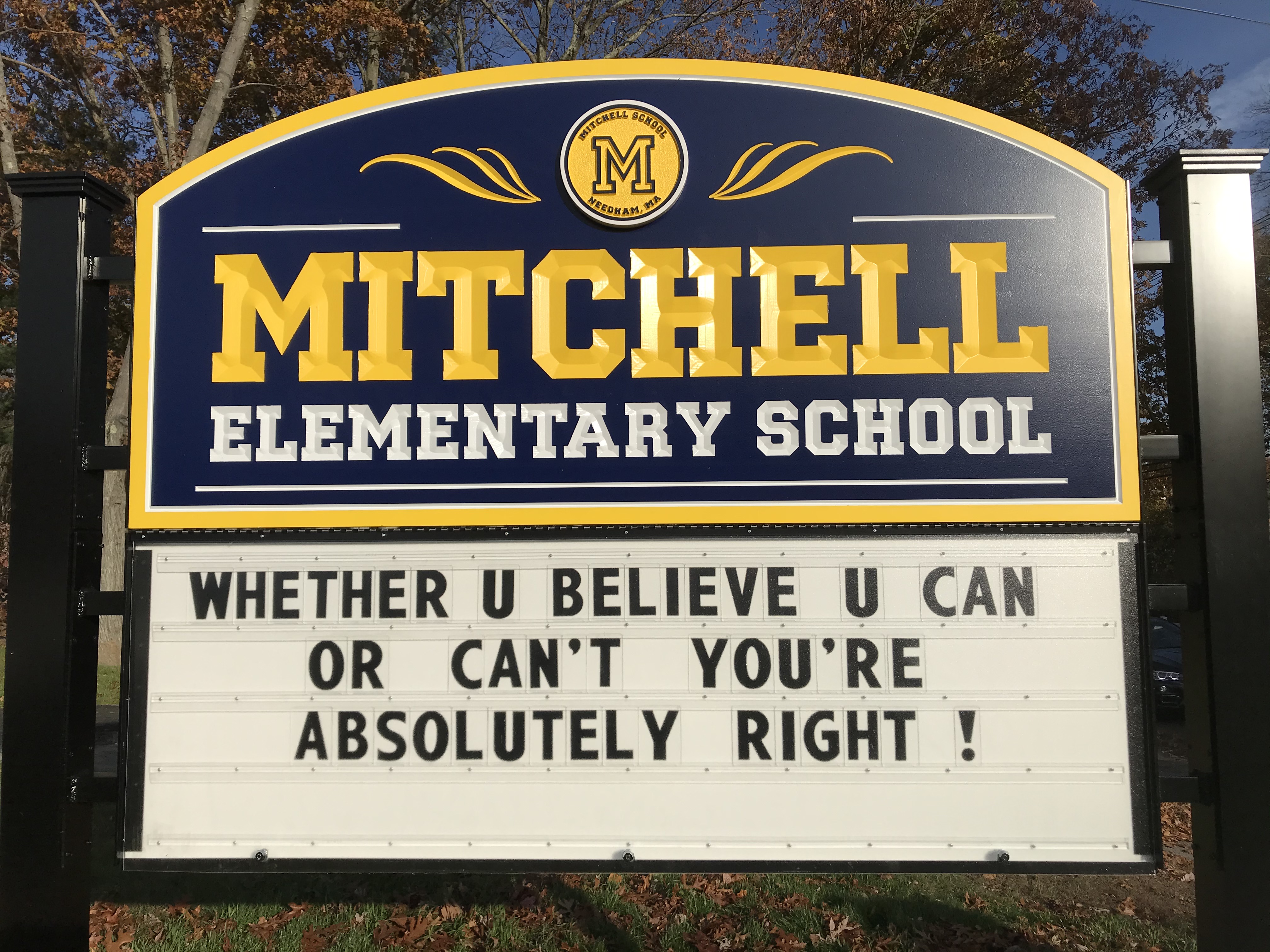

The message board outside Needham’s Mitchell Elementary School triggered a similar reaction when I passed by it earlier this month. “WHETHER U BELIEVE U CAN OR CAN’T YOU’RE ABSOLUTELY RIGHT!” What are we teaching the children in this town, I questioned, and I am not even referencing the problematic grammar that seems to acquiesce to the texting generation.

As someone who was raised on The Little Engine That Could, I can appreciate the power of motivational messages that encourage children to believe in themselves, show courage, and put forth their best efforts. After all, sometimes we sell ourselves short and assume something is out of our reach, when really we could have grasped it if only we took a chance and tried.

However, the little engine’s famous mantra is “I think I can,” not “I know I can,” and the difference of just a single word reflects a broad and important truth: While we can control our behaviors to an extent, outcomes depend on more than just our actions and are often subject to factors that are out of our hands.

Competitive runners learn that time is more in their control than placement, as the latter depends on who else is racing. For example, I may go into a race fully believing in my heart that I can finish in the top ten, but if the Kenyan national team shows up to run, all the self-belief in the world is not going to overcome my competition’s skill. Even finishing time, which is more in one’s control than placement, is still subject to exterior forces, such as weather, that can slow down the entire field.

Life experience has taught me that someone using the language of certainty, such as the verb “will,” when discussing outcomes that are only somewhat in their control is a red flag that the person has lost some touch with reality. One of my first jobs as a dietitian was at a startup medical clinic that boasted that they would expand to 50 locations across the country and build a headquarters complete with a farm and even their own medical school. The leaders disapproved of and took exception to pragmatic questions about the feasibility of their stated goals and used language of certainty when discussing the company’s future. A few years after I left the company, they went out of business completely, having expanded to a total of two locations.

My gripe with the quote outside Mitchell School is not technical, unlike the guy who used logic and mathematics to pick apart the semantics of Wayne Gretzky’s famous quote; nor is it theoretical, as if I were overly worried about a potential impact that may never come to fruition.

Rather, my concerns are based on real experiences I have had with my patients, including children, who cite these sorts of motivational quotes as justification for putting themselves in harm’s way. This most commonly occurs in the context of a desire to lose weight, as some children have told me that they believe they can lose weight and keep it off if only they try hard enough.

While I admire their self-confidence, which will likely serve them well in so many other areas of life, weight regulation is the wrong place to assume that belief in oneself and hard work is enough to get the job done. The truth is that while numerous methods of inducing short-term weight loss exist, nobody has demonstrated an ability to produce long-term weight loss in more than a small fraction of the people who attempt to achieve it.

Some research has found “almost complete relapse” after three to five years, other data are more specific and suggest 90% to 95% of dieters regain all or most of the weight within five years, while other research has found that between one third and two thirds of people end up heavier than they were at baseline. Research in adolescents has found that dieters were three times more likely than non-dieters to become “overweight,” regardless of baseline weight.

To suggest that the people who regain weight simply did not believe in themselves ignores the reality that behaviors play only a small part in weight regulation while factors out of our hands, such as genetics and our gut microbial population, are largely responsible. As an example, consider folks with atypical anorexia nervosa who can implement life-threatening levels of restriction without experiencing weight loss.

Unfortunately, striving for weight loss is not a benign pursuit in which the worst-case scenario means that one simply returns to where they started. Research has shown that weight cycling – repeatedly losing and regaining weight – is associated with numerous health problems, including a higher overall death rate and an increased risk of dying from heart disease, regardless of one’s baseline weight.

Teaching self-confidence is important, but I think we can do better than overly simplistic messages that children can – and will – take literally to their own detriment.